Fighting ‘The New Polio’ In An Era Of Defunded Science

Since 2014, a virus related to polio has paralyzed hundreds of children. Amid government cuts, what happens if the outbreaks worsen?

The safeguards that protect Americans from outbreaks and pandemics are being undercut. Illustration by Lucy Haslam

On an otherwise unremarkable September day in 2014, Luca, a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle-obsessed 4-year-old, had a fever.

Riley Bove, Luca’s mother, didn’t think much of it at first—a back to school cold, no biggie. Soon, though, Luca’s neck went limp like spaghetti—he couldn’t heave himself out of bed. Next, his arm went floppy: he couldn’t lift a glass of water to his mouth. That’s when Bove, a neurologist who, at that time, was wrapping up her training at Massachusetts General Hospital, grew worried.

“I don’t examine my own kids … I try to respect that boundary,” Bove says. But she also couldn’t unsee it.

She sent a video to a friend, who recommended they go to the emergency room—STAT. Bove was scared. She was also optimistic that this was all going to blow over.

“When you’re a physician, when [your kids] have a little thing, you’re like, this is a spectrum of nothingburger to fatal illness,” Bove says. Nothingburger is always the hope.

Within hours, though, Luca was on a breathing machine. Within a week, he was paralyzed head to toe. That still didn’t stop Bove’s spunky boy though. In the most difficult moments, Luca would manifest full Ninja Turtle, summoning whatever diaphragmatic strength he had to sing the superheroes’ battle song, one faltering breath at a time.

“Even the doctors involved didn’t anticipate it would get so bad,” Bove says, “there [was] panic—informed panic.”

Luca was eventually diagnosed with a then-little-known illness called acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM. In the long history of medicine, AFM is a relatively new disease—its debut in the academic literature came a decade ago. Since then, researchers have discovered how it happens through inflammation in the part of the spinal cord responsible for telling muscles when to contract. In that way, it reminds scientists of polio.

More recently, researchers have found another aspect of the illness that’s a historical throwback. Enterovirus D-68 (EVD-68), which is a cousin of the enterovirus that causes polio, emerged as the leading cause of AFM in cases where a cause could be identified. That connection has led scientists to lend EVD-68 a nickname: “the new polio.”

Since 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has tabulated over 770 confirmed cases of AFM. From 2014 to 2018, cases followed an every-other-year pattern of spikes and troughs. But then the fluctuations stopped. Since 2018, cases have numbered one or two dozen annually, compared to hundreds during prior peaks. (The virus has, however, continued to cause thousands of children to be hospitalized due to severe respiratory illnesses.)

While the jury is still out on why the previous pattern of spikes hasn’t returned, Dr. Kevin Messacar says it may be a function of good luck. Or evolutionary biology. Take your pick.

“There are a variety of theories … one is that the virus changed,” says Messacar, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado and founding member of the CDC’s now-disbanded AFM advisory group.

That wouldn’t be surprising, Messacar says. “Every virus changes over time,” he adds, “[and] if you think like a virus, causing [paralysis] is kind of a dead end.”

But according to Messacar, just because luck—or genetics—has smiled upon us since 2018 doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods forever.

“It’s just as likely that the virus could go back to causing neurologic disease as it would be to continue causing respiratory disease,” Messacar says.

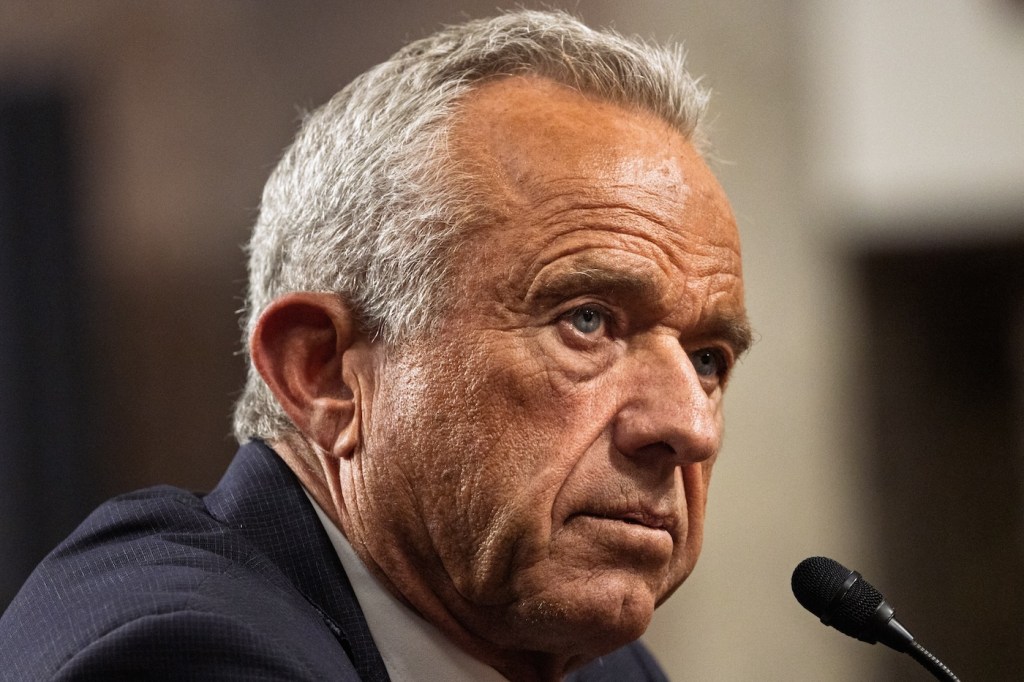

In a moment of widespread government funding and staffing cuts, that’s what worries people like Dr. Tom Frieden, an internal medicine physician and former CDC director under President Barack Obama. Because when it comes to EVD-68, over the past decade, we’ve made tons of progress. There are now widely available, relatively inexpensive tests for the virus, at least one promising treatment in the works, and even a couple vaccine candidates.

We’ve likewise made progress with many other pathogens capable of causing outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics. Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, the country has invested billions of dollars in preparedness efforts to make sure what happened in 2020 doesn’t happen again.

But amid “abrupt, poorly thought out, and devastating budget cuts,” our public health infrastructure “has been largely dismantled,” Frieden says.

As for preventing the next pandemic?

“I’m very worried,” he says. “The bottom line is, we are less safe.”

Pinning down EVD-68 as the culprit for AFM was no small matter according to Dr. Emily Erbelding, an infectious disease physician and director of the division of microbiology and infectious diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Back when those original outbreaks were happening in 2014, Erbelding says, most kids with a cough or runny nose—the symptoms that typically precede AFM—weren’t getting tested for EVD-68. To make matters worse, the virus wasn’t showing up in stool samples from patients who turned out to be positive. Nor was it in the vials of fluid that doctors had painstakingly extracted from the spinal cords of children paralyzed from AFM.

That meant identifying the virus was “a big puzzle,” Erbelding says.

As the outbreaks pushed on, samples pinged positive in Colorado, then in Norway, then in Alberta. Soon enough, scientists took to doing what scientists do: In 2017, American researchers infected mice with the virus, which subsequently developed AFM. By early 2018, Chinese researchers cloned the genes responsible for a signature protein unique to EVD-68, infused those genes into an otherwise harmless virus, grew that virus in the cells of a moth, blended the makeshift viruses into goo, sifted out the signature protein, injected it into baby mice, and found it prevented those babies from developing AFM. In other words, they’d found a vaccine.

“It took a lot of people coming together,” Erbelding says.

Messacar was among of the first. His group published the initial cases that appeared in Colorado. And he recalls that period with excitement and urgency.

“It wasn’t so much the intellectual curiosity of wanting to name a disease,” he says. “I had 12 families whose kids were normal one day, and woke up the following day and had parts of their body that were completely paralyzed … the emotional side of it was really about helping these families find answers.”

EVD-68 isn’t the first enterovirus to cause severe neurologic disease in addition to respiratory illness. For example, there’s enterovirus A-71, another cousin that often causes a type of the oh-so-common, oh-so-mundane hand-foot-and-mouth disease—but also has paralyzed children from California to Taiwan in the past 50 years. Then there’s polio itself, otherwise known as enterovirus C serotypes 1 through 3.

Part of the challenge with enteroviruses relates to their genetic makeup. They are single-stranded RNA viruses, which use molecular machinery that is particularly prone to error. “It’s like a faulty Xerox machine—a few letters are always going to be off,” Messacar says.

That, in turn, means they are notoriously quick to mutate, he adds. “The more copies it makes, the more errors it makes, the more variety of its progeny.”

According to NIAID, that means the viruses, as well as their larger family of Picornaviridae, are one of the small subset of “priority pathogens” that pose the greatest risk of a large-scale outbreak.

For Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Center for Health Security, there’s another foreboding characteristic of Picornaviridae: They were the one family of priority pathogens that seemed particularly resistant to COVID-era measures including masking and social distancing. That may be thanks to a variety of unique traits, like their ability to transmit through fecal matter and skin secretions beyond just respiratory aerosols, their tendency to live on surfaces for long periods of time, or their hyper-contagious capacity to jump from one person to another—even when the original host has minimal symptoms.

Taken together, the fact that outbreaks have been limited, especially since 2018, means two things to Adalja.

On the one hand, so far, “EVD-68 has not had all of those characteristics in the right formula to be able to cause societal level panic,” he says.

But on the other hand, EVD-68, like the rest of its family, has inherent “pandemic potential,” he says.

“It is definitely a virus that merits a lot of watching.”

“I am writing at the end of another very difficult week,” Dr. Ted Pierson, director of NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) wrote in an email on April 28.

The VRC has been a key contributor to what Frieden calls “a real golden age of vaccines” in the past couple decades. Particular successes in recent memory include immunizations for Ebola and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the latter of which demonstrated an up to 43% reduction in hospitalizations of children in its first year. To say nothing of the COVID vaccine: Within 24 hours of receiving SARS-CoV-2 isolates from China, VRC researchers pioneered research on the spike protein that subsequently formed the basis of the Moderna vaccine.

But since late March, the VRC has been hollowed out.

Under mandates by the Trump Administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), the center has steadily purged one-third of its contractors, according to reporting by Science.

Those mandates aren’t limited to the VRC.

DOGE has ordered the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which houses NIAID, to cut $2.6 billion in contracts. And the president’s 2026 budget proposal would slash funding for the agency by nearly 40%.

“NIH has broken the trust of the American people with wasteful spending, misleading information, risky research, and the promotion of dangerous ideologies that undermine public health,” the proposal states. (President Trump’s own Operation Warp Speed invested billions of dollars in the Moderna vaccine, which was premised in no small part on VRC/NIAID research.)

Other federal agencies responsible for pandemic response are facing significant cuts, too.

On March 27, the Administration announced that it would lay off 20,000 employees at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), about a quarter of the agency’s staff. The restructure included wholesale reform of several agencies responsible for pandemic preparedness.

On May 2, the presidential budget proposal brief—while claiming to “refocus[s] CDC’s mission on core activities such as emerging and infectious disease surveillance, outbreak investigations, and maintaining the Nation’s public health infrastructure”—simultaneously cut the agency’s budget by over a third. This includes eliminating the Global Health Center, which is responsible for monitoring and preventing outbreaks abroad, before they come to the US.

The budget reduction would also shutter the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP), which has funded everything from the March 2020 COVID response in Washington state to the Summer 2022 mpox outbreak response in New York City.

According to Adalja, these widespread cuts across federal agencies bear significant consequences for pandemic preparedness. “You have to think of response to infectious disease threats as an orchestra,” he says, “it has many parts, it has to be integrated and working as a whole—or you’re still vulnerable.”

The cuts have also impacted states. On March 24, the Trump administration terminated $11 billion of COVID-era public health grants to states—funds used for testing and response to the ongoing measles and bird flu outbreaks, among various other uses. “Now that the pandemic is over,” emails from the administration read, “the grants are no longer necessary.” And while that clawback is now on hold amid a temporary restraining order by a federal judge, to Frieden, those cuts threaten to “largely dismantle … the first line of defense” in America’s public health infrastructure.

“The bottom line is that anything that weakens state and local health departments … makes us less safe. It’s making America sick again,” he says.

“You don’t improve things by blowing them up,” he adds, “you improve things by improving them.”

Erbelding, for her sake, thinks we’re up to the task of another pandemic—at least on paper. She sees developments we’ve made in recent years, like Operation Warp Speed and wastewater monitoring, as potentially groundbreaking developments. “I think the United States has the tools,” she says.

That said, looking at all the cuts, Erbelding is concerned. “I worry about the possibility of a lot of different viruses changing over time and spilling over from animals, or gaining the ability for person-to-person spread and causing another pandemic,” she says, “[and] EVD-68 certainly stands out as a problem.”

Increasingly, it seems that preventing the next outbreak, from EVD-68 or something else, “is just a simple resource issue,” she adds.

Even as Washington, D.C., roils amid the cuts, and pandemic preparedness experts fear for the worst, on the other side of the country—in sunny San Francisco—Luca is thriving.

While he was hospitalized, doctors threw the kitchen sink at him: steroids, plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulins, experimental antivirals requiring single-use exemptions from the Food and Drug Administration. Slowly but surely, he improved. After about a month, he was stable enough to be discharged, and set off on the longer road to recovery.

These days, he’s an “incredible, very gregarious” teen, Bove says. After years of needing to use a neck brace—and being strictly limited from sports of any kind—he’s now riding bikes and playing soccer.

“On a good day, there’s kids in his middle school who never even knew he had a problem,” Bove says.

“They didn’t know what had happened him as a child … and they had no idea he wasn’t sort of ‘normal.’”

And on a bad day?

“[AFM] just really changed the course of his life,” Bove says, “his self-perception, his self-image, some aspects of his mental health, his identity, what he can do, you know?”

“Things that some people take for granted don’t happen,” she added, “for him, all of these things are big deals.”

Dr. Eli Cahan is a journalist and physician based in Boston.